The distributed web part 2: …or do you?

This is a follow-up to You Don’t Need a Website.

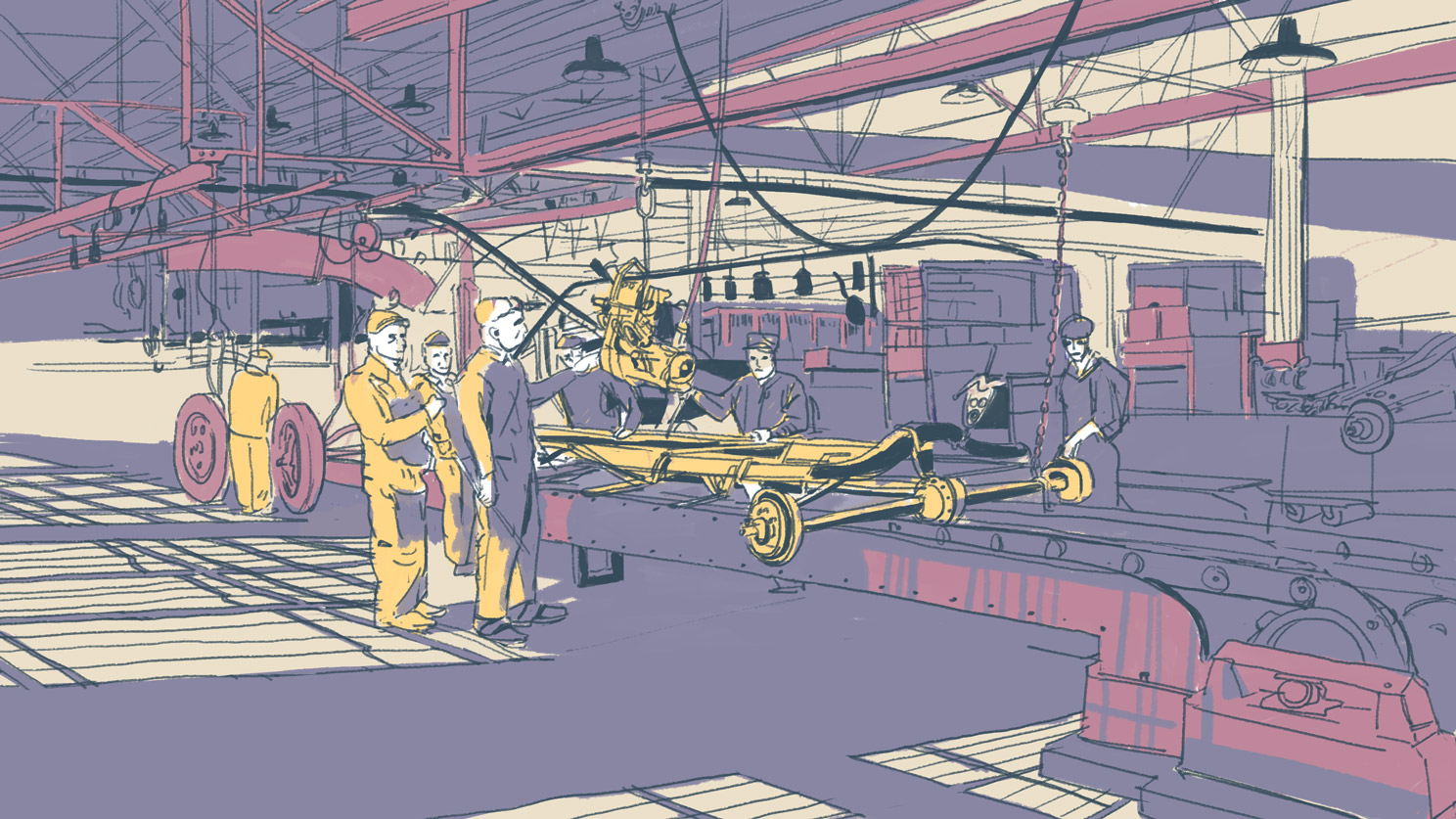

Building the Factory

Custom development boils down to one word: automation. It is simply the automation of a product or service, carried out by servers.

Custom development is much like an assembly line in a factory: work goes into designing and building this complicated mega-machine that assembles a product as rapidly as possible. It starts with a product that there is a demand for. Then, to meet that demand, the product is broken down into its elemental pieces. In the example of a car, each piece — engine, frame, wheels, transmission, etc. — is assembled individually and then pieced together into a finished product. When this concept of the assembly line first came out in the early 1900s (for those keeping score, it was not Henry Ford; it was Ransom Olds that patented the assembly line in 1901 for Oldsmobile), it reduced Henry Ford’s Model T production time from 12 hours to 93 minutes.

It’s efficient, to say the least.

But let’s put the product aside for a second and focus for now on the factory: in order to make a car engine, for example, imagine the machines necessary to cast the metal, drill the holes, and everything else involved from turning raw metal into a finished, machined part. Even if you don’t know anything about car engines, you can still acknowledge that the machines within a Ford Mustang factory have to be different from the machines within a Land Rover Range Rover factory simply because those are different automobiles with different sizes and different parts. To make different products, either the same machines must behave differently, or there must be different machines altogether. In other words, a factory — made of machines working together — is built and customized around a unique product, not the other way around.

For our last imaginary exercise, we’re going to imagine how much effort it would take to convert a Honda car factory into a gummy bear factory. Those things are nothing alike, you say. All factories use similar machines if we’re referring to the basic principles of mechanics, but instead of casting iron you’re now casting gelatin and high fructose corn syrup. Instead of drilling engine parts, you’re punching that little hole to slide the hanging plastic bag onto the hanger. And we’re not even mentioning food safety standards, at which your ex-car-now-food factory will spectacularly fail. In another instance, converting one type of car factory into a different car brand would take considerably less effort. But regardless, if the product changes, the machinery changes as well, to varying degrees based on the required change.

A web app is the factory; the product it produces is your product. Web apps are amazingly-efficient, custom machines built around delivering your product as rapidly as possible (milliseconds, to be exact). But unlike factories, web apps have the potential to be even more diverse and complicated from one web app to another. Web apps can do everything from scheduling a flower delivery (when is your mom’s birthday again?), to exploring the surface of Mars, to controlling robots remotely. But I don’t have to tell you all that the internet can do — after all, you’re using the internet right now (whoa!). Though it’s overwhelming to ponder all the paths down which custom development road can lead, it always starts at the same point: you’re building a web app around one — and only one — product.

What’s the product?

A unique scaffolding will be built around your product, and as the product changes and grows, sometimes a machine or two will need adjustment.

If your understanding of your own product is cloudy, how do you expect an application to automate it? Imagine you are trying to mass produce your own car line, but you haven’t decided on a transmission type. Halfway through construction of a factory engineered to produce 5-speed cars, you change it to 6-speed, then wonder in dismay as the project suddenly skyrockets over-budget and past deadline. I only changed one thing, you say, without realizing that one decision affected the driveshaft, gearbox, dashboard interior, onboard computer, and a plethora of other things this particular article writer doesn’t fully understand about cars.

Continuing the discussion from Part One, remember that you’re at the point of custom development because there’s absolutely no other service in existence that can deliver your unique product. There’s no factory that can assemble your wares. So you’re building your own, which means a very large, complicated thing now depends on the tiniest details of your product.

To be clear: you don’t have to know the first thing about web development. That’s our job (and we’re open about our discovery process and how we start projects). But you, as a client, are responsible for two things:

- Knowing your product intimately

- Understanding that what we build is customized to your unique product

Just because code isn’t physical — like a building — doesn’t mean it’s any easier to change its structure. Much like the thousands of girders of a building are meant to support its unique structure, or like the thousands of moving parts in a factory are designed to yield only one product, the thousands upon thousands of lines of code in an application are similarly designed to yield one specific product.

I should mention: to those that know the craft, there are some changes the structure affords with little difficulty. There are some changes a product may undergo as it evolves and grows, and, yes, sometimes a machine or two will need adjustment that impacts scope for the sake of product improvement. This is one of the reasons we at Envy bill hourly and don’t engage in fixed-bid projects. But the more strategic and focused your changes are, the more you’ll lessen the negative impact of change, and the more time and money you’ll save in the development process. If, in the transmission example above, the request was motivated by a desire for fuel efficiency, we’d suggest instead a more optimal wheel diameter that is similarly effective in gas mileage savings (source). But our solution, by comparison, caused virtually no setback because cars are designed to accept a range of wheel diameters.

It’s as much your job to know your product as it is our job to guide you through improvements as efficiently as possible that support and enhance your product rather than cause constant upheaval.

Where should we build?

Your next question is undoubtedly how much does custom development cost? _You probably also knew this was coming: _it depends.

As much as I’d like to break down a formula for development, it really does depend on your strategies as a business, much like it matters whether you’re opening a gummy bear factory or a motorized prosthetic hand factory. Determining cost depends on what type of development you pursue, of which there are 3 major types:

- Web Apps (dot-com-based)

- Native Device Apps (iOS, Android)

- Native Desktop Apps (Mac, Windows)

The next question to answer is where / how do your users need to access your product?

The best bang for your buck is web apps, because those are accessible on any device: mobile, tablet, laptop, and desktop. But web apps aren’t a silver bullet for everything as they require an always-on internet connection that native applications don’t. As a designer, I couldn’t imagine needing internet to run Illustrator from my laptop as I kill time in the passenger seat of a car. If I am looking up a rock climbing guide for a particular area, I don’t want to bring my laptop if my phone will do, and I probably won’t have an internet/cell phone connection when I need the guide most, either.

So is native development the way to go? Not always; native development requires a large investment for you to silo your product into one specific type of device such as iPhone or Windows PC, and if that device receives a major update or just dies completely, you have to re-invest all over again. If, for example, you developed an online shopping experience only on Android, you may find your customer base severely limited. Alternately, if you developed a learn-to-code website such as Code School, it’s safe to assume users have a steady internet connection and would want a full keyboard anyway — web app is the way to go here. Understanding on which devices your users need your product, and the times / conditions during which most people use your product makes the decision clearer. There’s not a universally correct answer; the end result is always as unique as your product.

We’ll go into each of the three development types in greater detail in future blog installments — there’s a lot to talk about for each of those three, and we haven’t even scratched the surface.

Recap

The end result is always as unique as your product.

Maybe this blog post didn’t give you the clearest picture about the finer details of custom development, but remember: it’s always about your unique product, and no one else’s. The next step is to find a development agency to build your product, but before you get there, these are the most important questions to answer as the foundation for custom development:

- What is my product?

- How does my product absolutely require an online component?

- Do I know my product well enough that it won’t change as I’m paying for development of a web app / native app?

- How will users need to use my product — desktop? Mobile phone on the go?

- Am I willing to pay for development for native development for multiple devices?

If Henry Ford could increase his product output by 800% with automation in 1913, just imagine what custom development could do for your product in 2016.

You bring the product; we’ll handle the factory.