There’s no such thing as multi-axis modes

The two best days in a design system designer’s life is the day they inherit the design system, and the day they get rid of it. Or so the saying goes.

A la mode

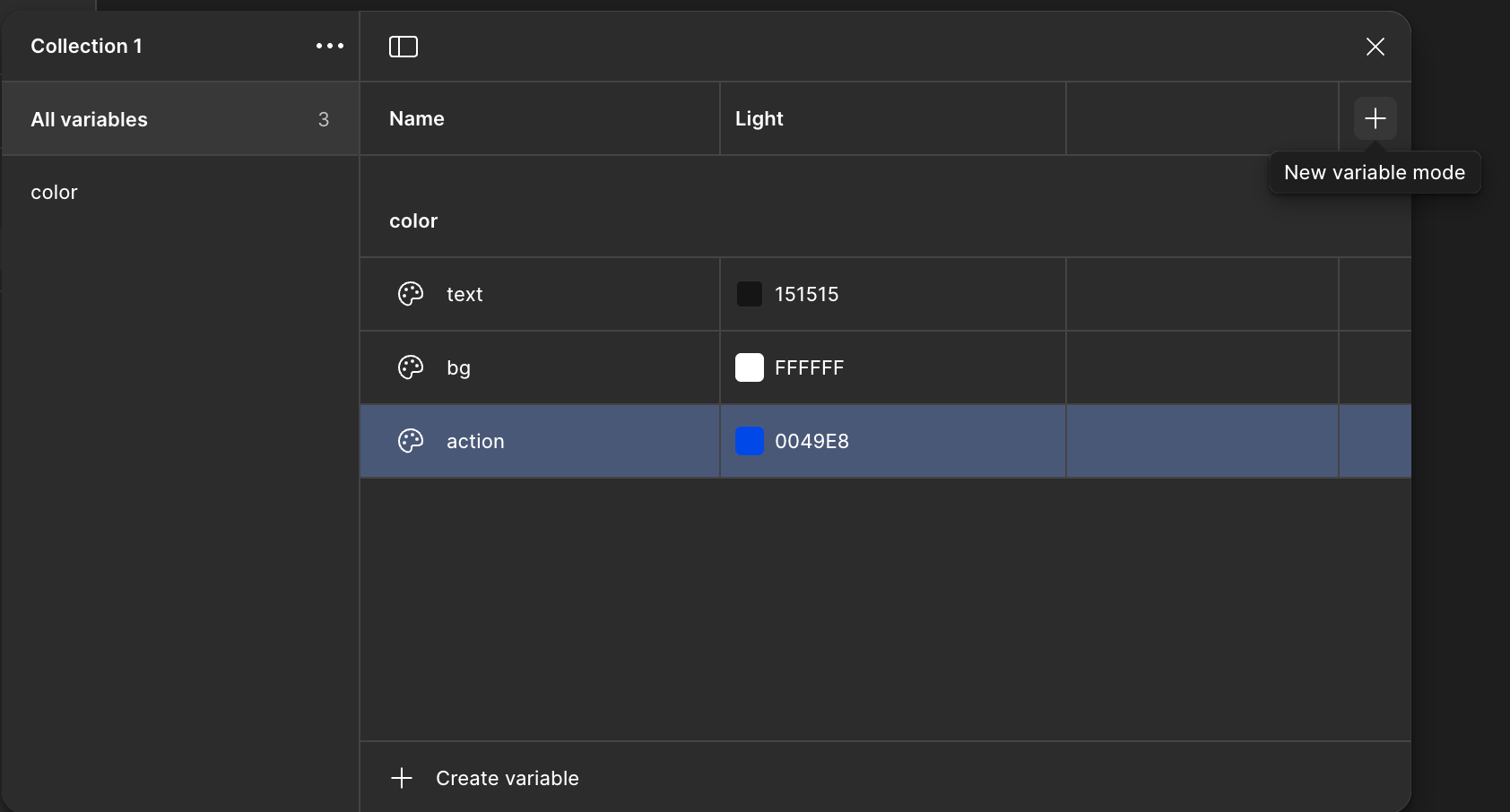

When you start managing design tokens for your system, there comes a point when you make the leap from light mode to dark mode (or the rarer dark-to-light). Figma makes this simple—just click that little plus sign in the Variables panel and get to work!

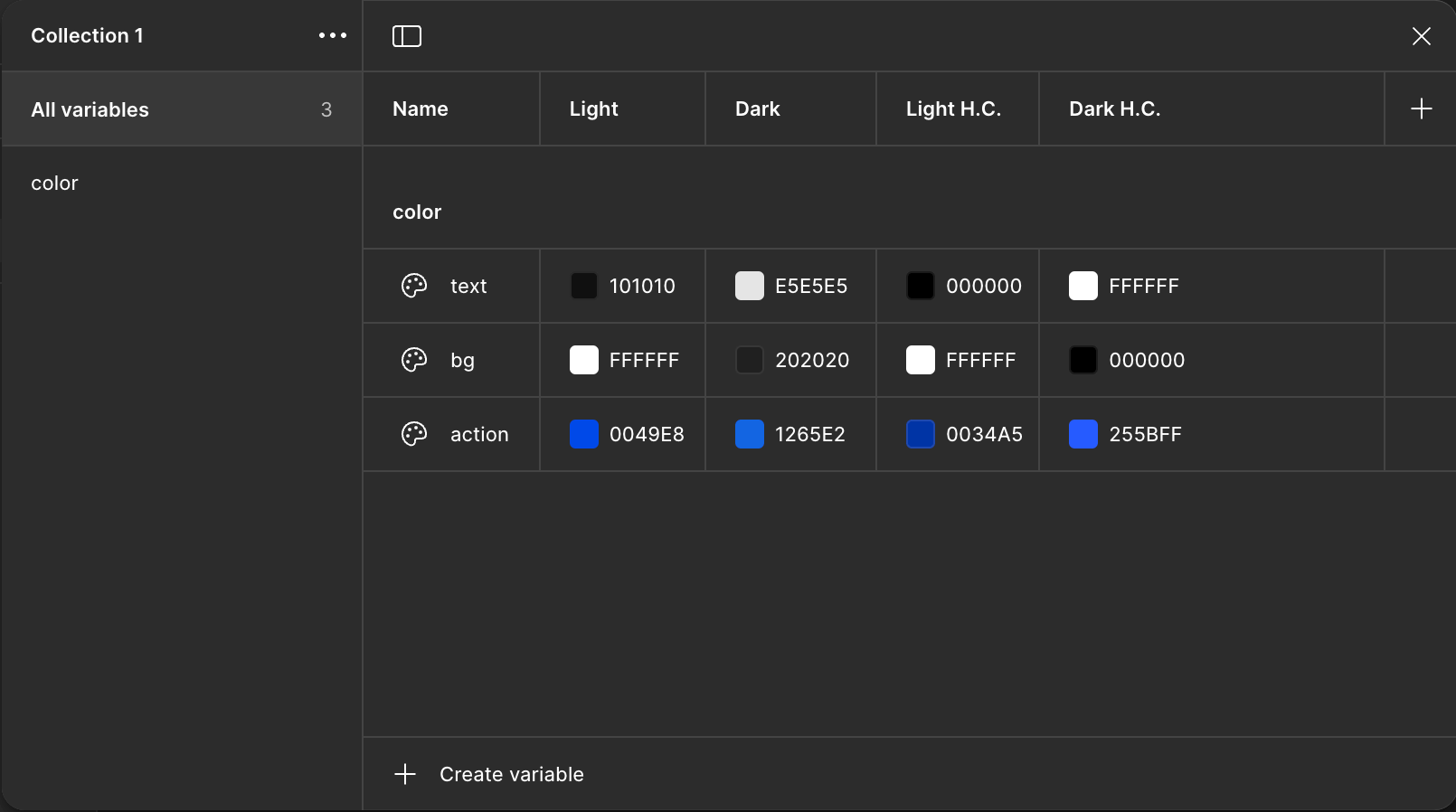

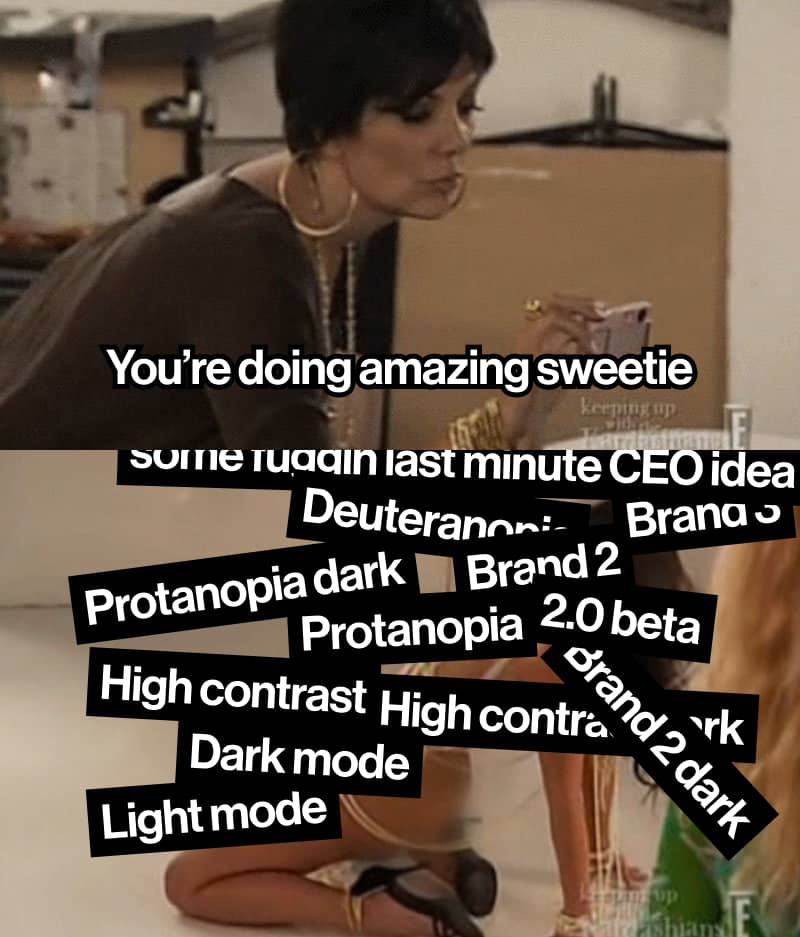

But by the time the third and then fourth mode rolls around, you start feeling the pain. “That’s ridiculous!” some of you may be thinking. “When would you even need a third mode after Dark Mode?” Glad you asked! Here are several common scenarios that lead to multiplying modes:

- Accessibility. Need a high contrast theme? Now you need alternate versions of light and dark mode that pass WCAG standards.

- Color blindness. Protanopia/deuteranopia and tritanopia users exist! Good news is protanopia and deuteranopia are similar enough they can share a set. Bad news is that all your existing color tokens still multiplied by 3.

- Multi-brand. That new startup your company acquired had its own design system you need to incorporate.

Mind you, these are not exclusive scenarios—some companies undergo all 3, or more. And every time you add on a new layer, it multiplies the number of existing color tokens you have.

Editor’s note: I was going to make another graphic here that had 8+ columns, and

the columns would have increasingly-desperate sounding names like “oh god,”

“oh fuck,” etc. But I got paywalled by Figma (yes, my own company), because even

they have a limit on how many values they can maintain before charging more $$$.

The problem exists on both sides—it turns out having a button that when clicked

multiplies your number of database records isn’t great software architecture

either. At least both devs and designers agree on this!You can see how 0 → 1 layers, or “axes,” was a non-issue. But going 1 → 2 and beyond starts to topple your system. It accelerates to a point that you can’t hire fast enough to maintain it, even assuming you had the budget in the first place (you don’t). “There must be a better way,” you say.

Multi-axis-whosie-whatsie?

There isn’t a better way. Thanks for reading! Bye-bye!

“…What? Are you serious?”

Unfortunately, yes. Let’s take another look at trying to come up with a “clever” solution, and we’ll see it doesn’t work.

We’ll keep the scenario of going from 1 → 2 axes, the first being Dark mode and the second being High Contrast mode.

Failed attempt 1: the cascade, but worse

Breaking out of Figma, and going into CSS, we realize the problem immediately: trying to declare a 2×2 matrix in only 3 selectors proves to be a challenge:

[data-theme="light"] {

--color-text: #101010;

--color-bg: #ffffff;

--color-action: #0049e8;

}

[data-theme="dark"] {

--color-text: #e5e5e5;

--color-bg: #202020;

--color-action: #1265e2;

}

[data-highcontrast="true"] {

--color-text: #000000;

--color-bg: #ffffff;

--color-action: #0034a5;

}

/* ❌ What happens for <div data-theme="dark" data-highcontrast="true">? */We realize data-highcontrast only works for light mode, and not dark mode. We shaved down our modes from 4 → 3 by *checks notes* deleting one. We were trying to handle <div data-theme="light" data-highcontrast="true">, and wanted to get <div data-theme="dark" data-highcontrast="true"> for free, but it didn’t seem to happen this go-round. “Hm. I’ll have another go.”

[data-theme="light"] {

/* … */

[data-highcontrast="true"] {

/* … */

}

}

[data-theme="dark"] {

/* … */

[data-highcontrast="true"] {

/* … */

}

}”I’ve done it!” you say, a half-second before realizing you are back at the number of tokens you started with. What’s more, you’ve created a scenario where now [data-theme] and [data-highcontrast] can’t even be on the same HTML element! “No, no, wait—I’ve got it,” you say.

[data-theme="light"]:not([data-highcontrast="true"]) {

/* … */

}

[data-theme="light"][data-highcontrast="true"] {

/* … */

}

[data-theme="dark"]:not([data-highcontrast="true"]) {

/* … */

}

[data-highcontrast="true"][data-highcontrast="true"] {

/* … */

}You’ve fixed your cascade issue, but are still stuck at the same number of tokens. In fact, try this at home—try and come up with a scenario where you can express a 2-axis system (2×2 matrix) in CSS with only 3 selectors. Any system you engineer will have some problem with cascading, or have colors ultimately missing that will lead to a bad experience.

Failed attempt 2: in color space, no one can hear you scream

“Well, of course you wound up with the same number of tokens—you had created all those hex codes manually in the first place! The real solution is in generation.”

Asking color science to fix your problems has historically never worked for anyone. But maybe it will work for us here!

:root {

--color-text-h: 0;

--color-text-s: 0;

--color-text-l-light: 6;

--color-text-l-dark: 90;

--color-bg-h: 0;

--color-bg-s: 0;

--color-bg-l-light: 100;

--color-bg-l-dark: 12;

--color-action-h: 221;

--color-action-h-dark: 216; /* wait, fuck, the designer shifted the hue? fuck */

--color-action-s: 100;

--color-action-l-light: 45;

--color-action-l-dark: 45;

}

:root {

--color-text: hsl(

var(--color-text-h),

var(--color-text-s),

var(--color-text-l)

);

--color-bg: hsl(var(--color-bg-h), var(--color-bg-s), var(--color-bg-l));

--color-action: hsl(

var(--color-action-h),

var(--color-action-s),

var(--color-action-l)

);

}

[data-theme="light"] {

--color-text-l: var(--color-text-l-light);

--color-bg-l: var(--color-bg-l-light);

--color-action-l: var(--color-action-l-light);

}

[data-theme="dark"] {

--color-text-l: var(--color-text-l-light);

--color-bg-l: var(--color-bg-l-dark);

--color-action-h: var(--color-action-h-dark);

--color-action-l: var(--color-action-l-dark);

}

[data-highcontrast="true"] {

--color-text-l: calc(1.2 * var(--color-text-1));

--color-bg-l: calc(1.2 * var(--color-bg-1));

--color-action-l: calc(1.2 * var(--color-action-1));

}“I am so clever,” you say, before realizing this doesn’t work at all. Not only is it an incomprehensible mess (for only 3 tokens), this is not how CSS works.

- When CSS variables compose other CSS variables, they have to be redeclared. In

:root,--color-textdoesn’t work becausevar(--color-text-l)isn’t defined until later.--color-texthas to be redeclared in every selector to resolve to a color (which means, ding ding ding we need that 4th selector back) - You can’t simply

calc()into Mordor.undefined × anything = undefined. - Further, even if

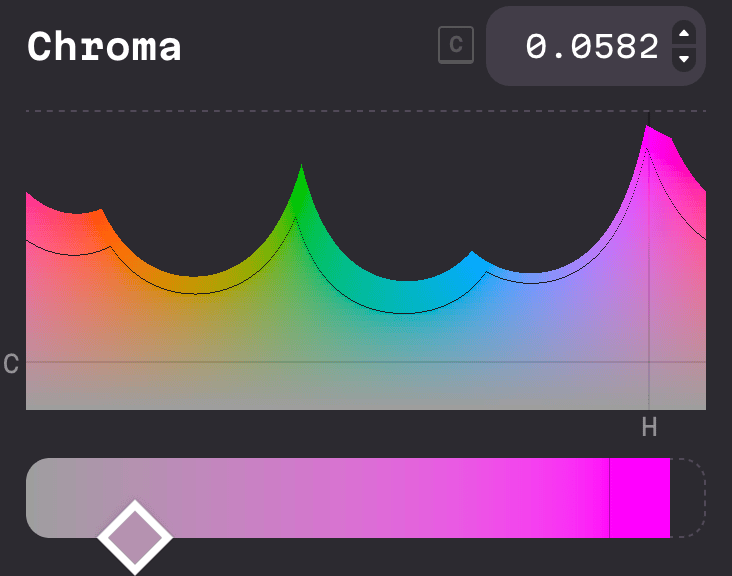

calc()did work in some alternate universe, HSL is dogshit, so any formula that works in light mode won’t work at all for dark mode. It’s a completely different calculation.

I know you already get the point, but just to drive the nail through to the absolute center of the earth:

“Oh, it was just the HSL space that’s bad. What if we used LAB?”

LAB is not perceptually-uniform like Oklab/Oklch

“OK, we’ll use Oklab/Oklch, then.”

The WCAG 2.2 standard is based on LAB (D65 whitepoint) so we won’t pass

“Is there a better standard than WCAG?”

Not at the moment, unless you count APCA, which is a candidate for WCAG 3 but is currently proprietary/closed license. Also WCAG 3 doesn’t exist yet.

The TL;DR about color science is human eyeballs are weird, and RGB screens are limited. That means there is no magic math that will produce 2 axes’ worth of colors, let alone more. You are welcome to try and prove me wrong! But beware it will take a bigger time investment than you realize.

Failed attempt 3: magic?

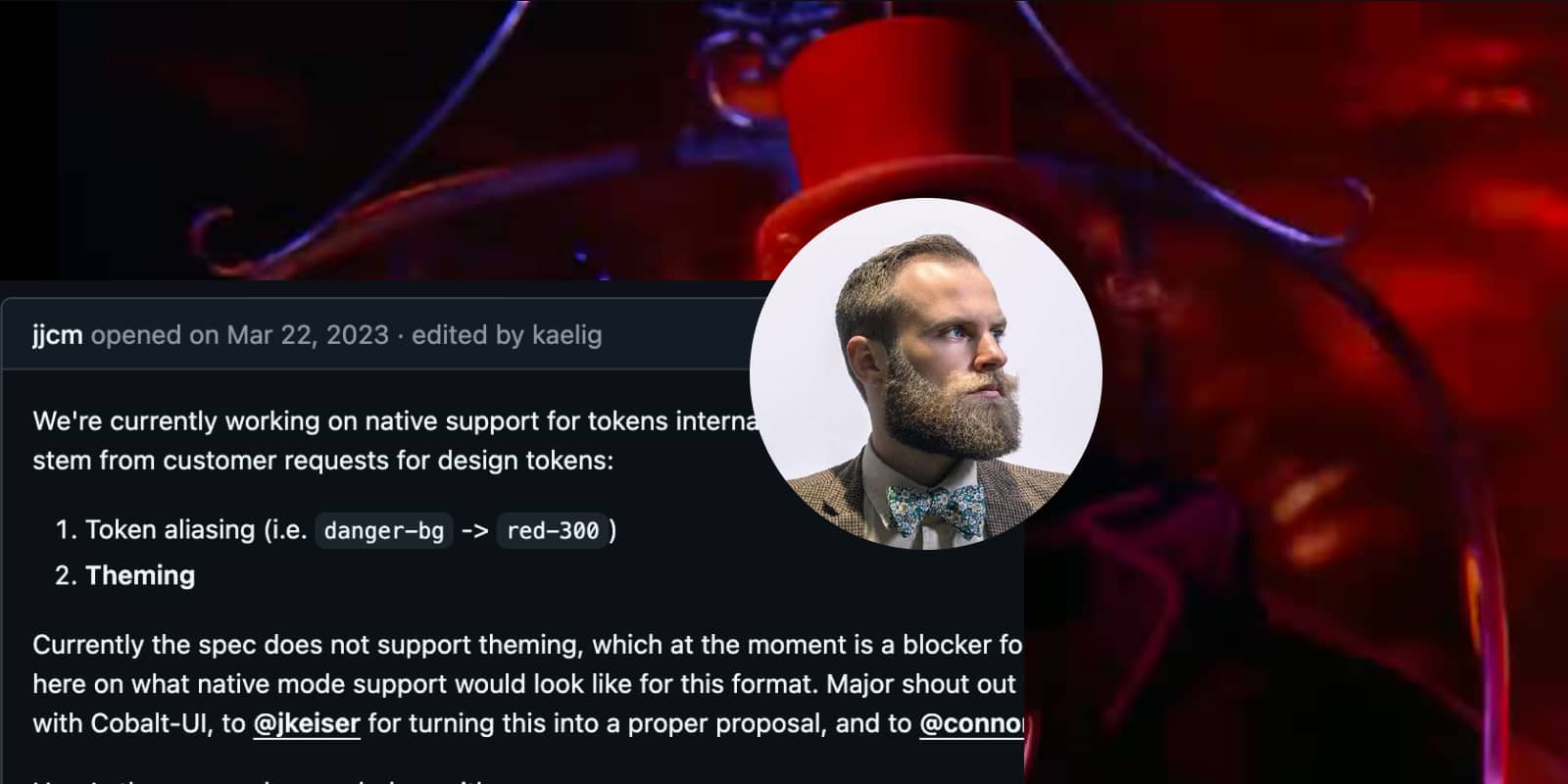

I’m now an author on the Design Tokens Spec which happened because I read every kooky comment posted on the GitHub repo. The kookiest of which was #210: Native modes and theming support, a 60-comment discussion where the smartest design systems thinkers on the internet collectively descended into the depths of madness trying to solve this problem.

I was mentioned in comment #1 on that thread which meant I was dragged down to the pit of hell along with everyone else. For those that haven’t read it, here’s a brief 3-part visual summary:

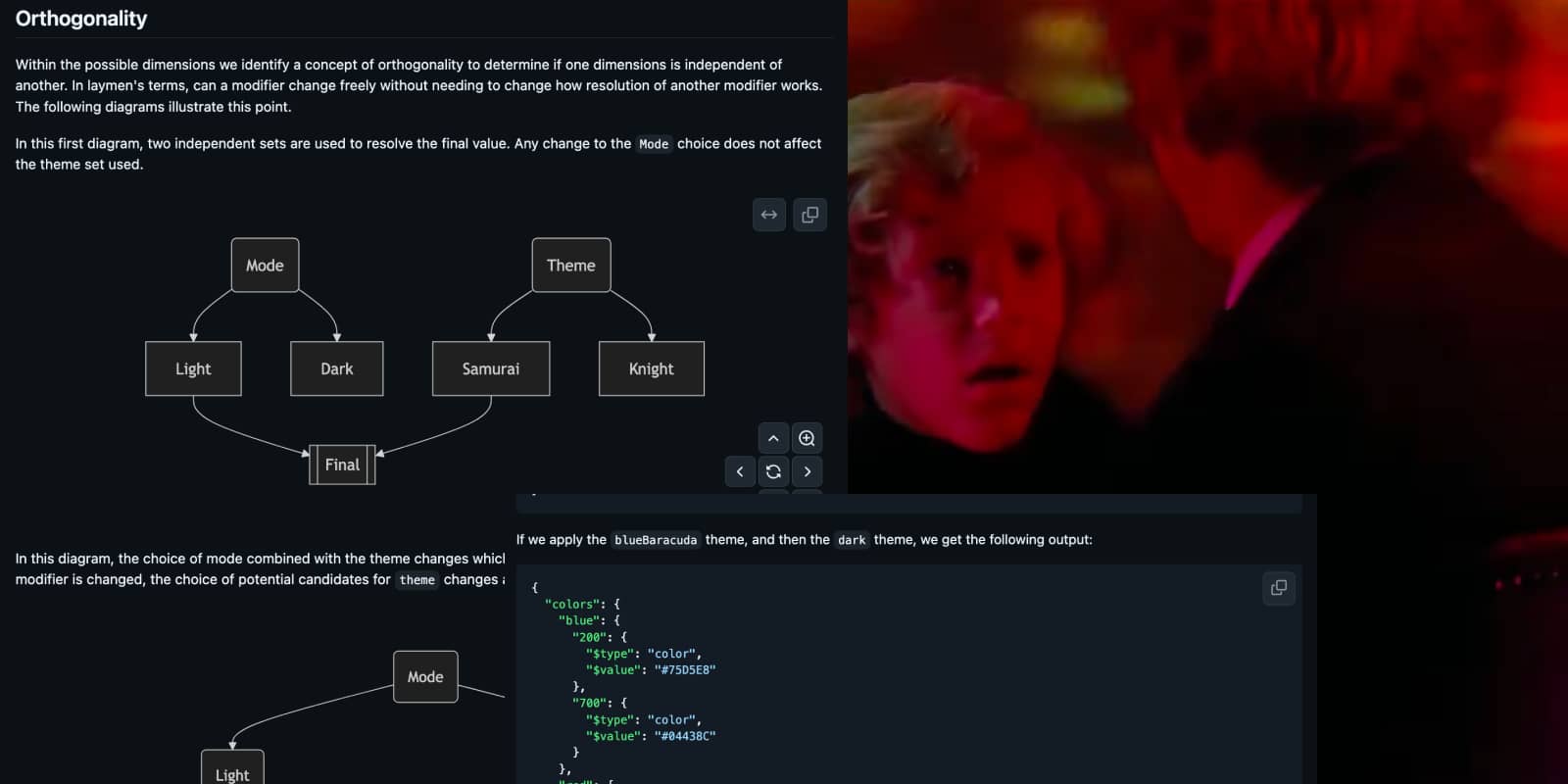

Anyway, about a year later, all of that debate coagulated into a proposal to solve this problem called The [Token] Resolver proposal. It describes a mechanism by which token themes can be declared using the absolute minimal syntax possible. It came from Tokens Studio and folks that had dealt with this problem at scale, for years. It has been reviewed by many smart folks. It has also been reviewed by me (not a smart folks). I even made a working interactive implementation of it.

What it does solve:

- Token duplication across modes

- Theme support for people using the Design Tokens Spec in a backwards-compatible way

- A code-friendly way to describe Figma Variables and Tokens Studio variables

What it does not solve:

- The problem outlined at the beginning of this blog post

The rub is, even with really fancy abstractions on top, in the end the computer is still going to ask “what color does this need to be?” And if you don’t know, neither will it.

The Resolver spec is really cool. And it is magic how it can remove all duplicate tokens in your system, leaving the minimum number necessary to manage. But removing duplicates doesn’t change that underlying 2D “spreadsheet” like how Figma Variables works today. That’s just the system itself.

“No, no, no! You’re just not getting it! Instead of multiplying every token in a single plane, we’ll just create a new ‘axis!’ Then we only have to declare 1 token per plane!”

Brilliant. You’ve succeeded in breaking out of the 2D token spreadsheet, and have entered the 5th dimension. Have fun organizing 5-dimensional tokens into your 2-dimensional UI. Idiot.

No, really. help.

Multiple axes may have been a dead end, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make some slight improvements to the 2D spreadsheet to make it a little more manageable. Perhaps this will happen in Figma Variables, perhaps it won’t. But either way, the 2D spreadsheet is here to stay. If the spreadsheet feels complex, it’s because you’re doing a lot! And it is complex. And you should feel amazed at yourself for handling such a complex thing.

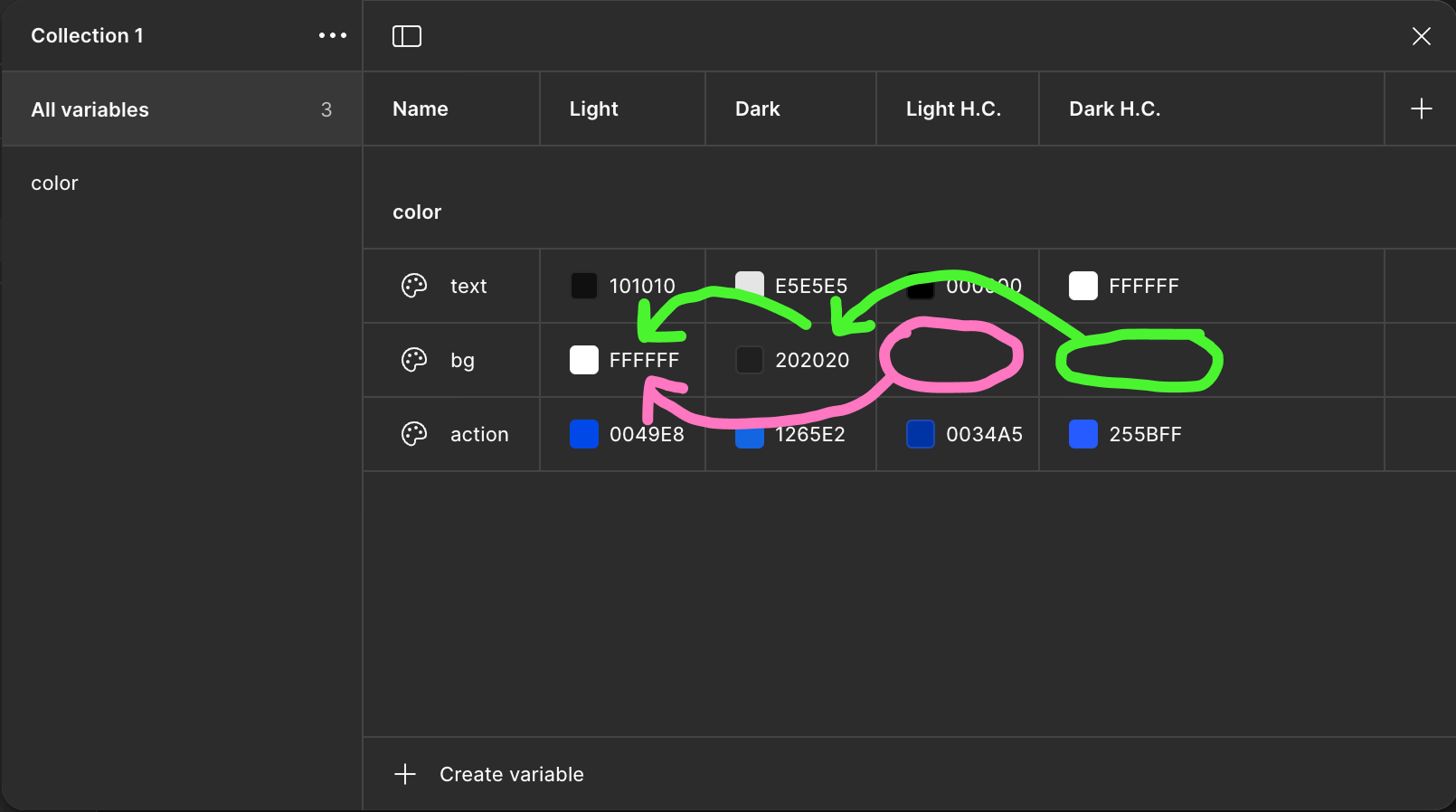

The best we can do for now is declare mode fallbacks. A “fallback” is different from an alias, where one token value points to another. A mode fallback allows a mode to leave “gaps” in token definitions, but declares “if a token is not defined here, try Mode 𝑥. If Mode 𝑥 doesn’t have it, try Mode 𝑦,” and so on, until we eventually hit a value. Figma Variables doesn’t support this yet, but is actively working on a similar mechanism (name TBD). To visualize it in the Figma Variable table, it would look something like this:

Mode fallbacks are like a swiss cheese model of sorts, where each mode is allowed to have “holes.” But when you have multiple layers, with the holes being in different places, you cover all the gaps across all modes.

Sure, it’s maybe not the revolutionary change you were hoping for. But it’s about as simple as any system can get while leaving you in full control.